Wetlands in the Stour Valley

The Stour Valley contains a variety of wetlands of value to birds, aquatic mammals, amphibians, insects and plants.

They vary in size from the smallest village pond to large reedbeds and marshes. The most valuable wetlands are often those where a number of related habitats exist together, as at Stodmarsh National Nature Reserve, where the reedbeds, grazing marshes, wet woodlands, lakes and ponds together constitute a site of international importance for wildlife.

A number of factors determine the character and value of a wetland. The quality of the water is important – whether it is nutrient rich or poor, whether it is alkaline or acid. Acid waters feed bogs, while fens depend on alkaline water. The amount of water, depth and seasonal variations also play a big role: ponds and lakes tend to hold a depth of water all year round (although some ponds dry out in summer); reedbeds grow in ground that is waterlogged for most of the year, while marshlands tend to be wet only in autumn and winter; many grazing marshes have been drained with networks of ditches and will only flood in wet winters, but the ditches are valuable habitat. Management is the other big factor that shapes wetlands and is usually required to maintain important habitats. For example, an unmanaged reedbed will eventually turn to wet woodland. Not only is human management important for wetlands but many of them were created by human activity – for example the many lakes found close to the Great Stour are flooded gravel workings.

Unlike woodlands and grasslands, wetlands don’t have to be old to be of value. New wetlands can become excellent habitat for all kinds of species after just a few years.

Floodplain wetlands

Riverside habitats are a particularly important feature of the Stour Valley. Grazed riverside pastures are a characteristic sight. Flood meadows, old pollarded willows and bankside vegetation all offer habitats for a range of species, and benefit the wildlife of the river itself. However, on many parts of the Stour, trees have been grubbed out, meadows drained, and arable crops planted right to the edge of the water, primarily to increase agricultural production. The river itself has also been altered – straightened and made less natural. More positive is the creation of several lakes in the valley. These flooded industrial gravel workings are now habitats for birds and a range of other wildlife.

Related KSCP projects:

Great Stour Meadow

Hambrook Marshes (Photo: Will Hirstle)

Grazing Marsh

Grazing marshes are low lying wet pastures. They often flood in winter, attracting migratory birds, and their network of drainage ditches provides habitats for aquatic plants and insects. In recent years, many grazing marshes have been drained much more effectively by modern pumping systems, which makes the land suitable for arable crops (more profitable than grazing), but destroys much of the wildlife interest. Having said that, the ditches may remain valuable habitats.

Worth Marshes near Sandwich (Photo: Will Hirstle)

Reedbeds

Reedbeds occur on land which is flooded for most of the year, often at the edges of lakes or in shallow lagoons. Dominated by a single species of reed – usually common reed – they are habitats for specialised wildlife, including some very rare birds. They have been lost with the widespread drainage of land for agriculture.

The Stour Valley contains some of south-east England’s largest reedbeds, at Stodmarsh National Nature Reserve.

Reedbed at Stodmarsh

Ponds

Ponds were once a common site on farmland, supplying water for livestock and providing habitats for amphibians and aquatic plants. However, as agriculture has changed in recent years, many have been filled in or neglected.

There are ponds throughout the Stour Valley (although few in the Kent Downs). Visit Buxford Meadow, Ashford Warren or Chilston Pines and Ponds to see some particularly good ones.

Pond at Hambrook Marshes

Related KSCP Projects:

Hastingleigh pond

Kingsnorth ponds and scrapes

Bogs and fens

Bogs and fens are both types of mire – a mire being an area of permanently wet peat caused by a water table very near the surface or (more usually in the north and west of Britain) by high rainfall. Where the water supply to the mire is acidic, bog vegetation will result. Where the water is alkaline, fen vegetation, which can include very diverse plant communities, arises. Both are extremely rare habitats in Kent but are present in the Stour Valley.

Kent’s last remaining valley bogs can be seen at Hothfield Heathlands and the county’s last old fen is at Ham Fen (access by arrangement only).

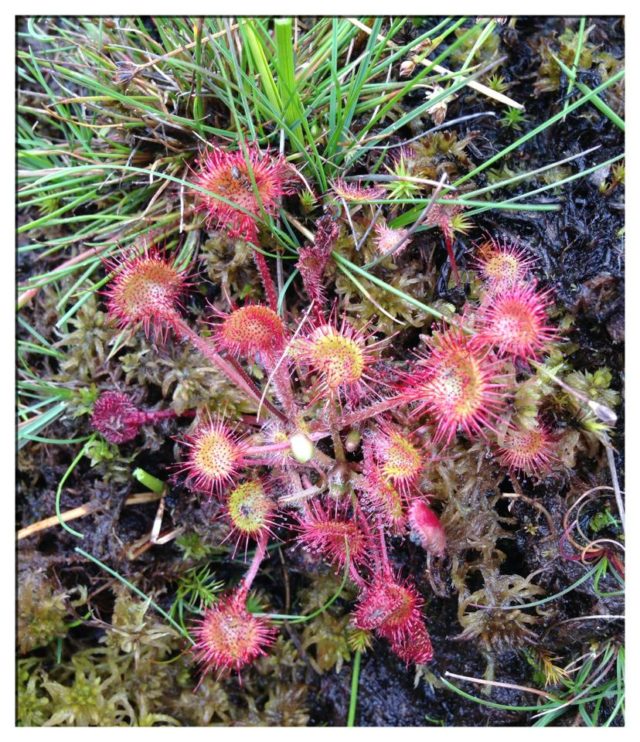

Round-leaved sundew – a rare bog plant at Hothfield Heathlands (Photo: Gabrielle Lindemann)

Wet woodland

Wet woodland is another scarce habitat that has disappeared from many areas. It is home to several notable insects, particularly those that require dead wood in water to breed. Mosses, liverworts and fungi also thrive in these conditions. Wet woodland tends to consist of very few tree species – usually just alder, willow and birch, and in the Stour Valley ‘alderbeds’ of just alder are quite characteristic.

Stodmarsh National Nature Reserve contains large areas of wet woodland.

Willow carr – wet woodland