The River Stour

Introducing the Kentish Stour

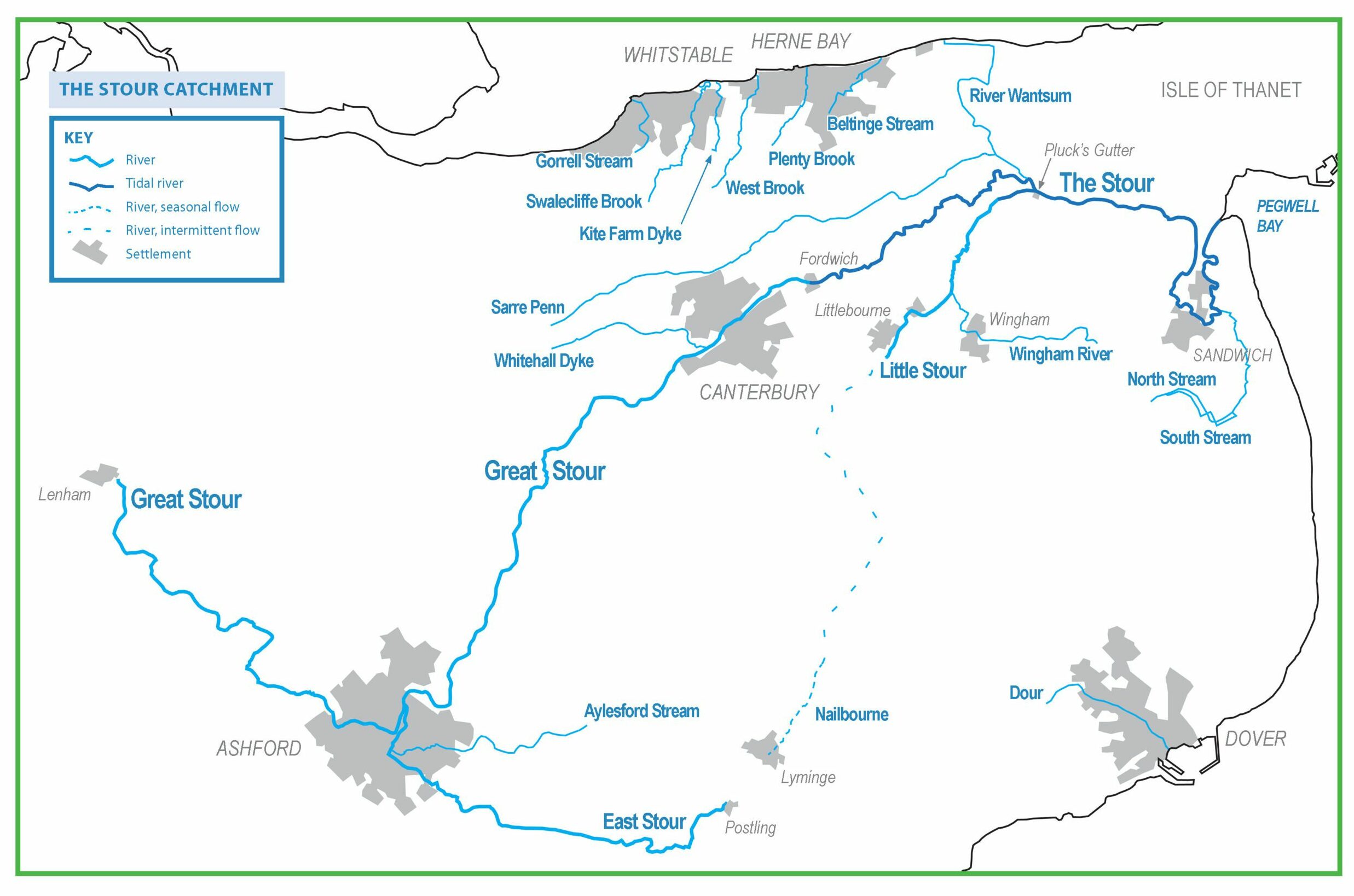

The Kentish Stour is the major river catchment of East Kent. Its largest river is the Great Stour, the second longest river in Kent (58 miles), which has its source near the village of Lenham and flows out to sea at Pegwell Bay. The Catchment encompasses many other watercourses from the smallest streams to major tributaries like the East Stour.

The Kentish Stour is an important river system, of great value to human and natural communities alike. It supplies water for agriculture and industry, provides drainage, recreation and wildlife habitat. Some of its rivers are chalk streams of global significance. Some flow through areas of international importance for conservation. Most pass through settlements; loved and celebrated in some places, flowing underground and forgotten in others. They are part of the history and folklore of this part of Kent and have powered industries in the past.

In an ideal world, all the rivers of the Stour Catchment would be shaped by natural processes, with good water quality and abundant wildlife. In a few places these conditions exist but for the most part, these rivers face many challenges: pollution, low flows due to the demand for water supply, invasive species and the legacy of structures left by old industry. Despite these pressures, the Stour Catchment’s rivers are still great places for walking, recreation and wildlife watching. In many places they have tremendous beauty and natural diversity. They are homes for many well-loved and sometimes declining species.

The Kentish Stour Countryside Partnership is at the forefront of efforts to improve rivers in the Catchment, working together with a range of other bodies, with landowners and the community.

Upper and Middle Great Stour

The Great Stour starts its journey as a number of small springs near the village of Lenham. From here it travels in a roughly south-easterly direction. Despite flowing over the rocks of the Greensand Belt, it has many of the characteristics and species of a chalk stream.

The river is rural and the channel is quite natural in many parts and good for wildlife, although surrounding agriculture does impact on water quality. It flows through attractive settlements like Little Chart, and through scenic Godinton Park. It then enters it’s first major town – Ashford – running through the Ashford Green Corridor. It changes direction, now heading north-east, before being joined by a major tributary, the East Stour.

The Great Stour leaves Ashford then flows into a breach in the North Downs called the Wye Gap. From this point, it becomes a true chalk stream, flowing through the Downs in a wide valley. Beautiful riverside spots include Olantigh Park, Godmersham, and Chilham Mill. Running past Chartham and several flooded gravel workings, the Great Stour flows into the historic cathedral city of Canterbury, passing Hambrook Marshes and the Westgate Parks on the way.

Lower Stour

The confluence of the Great and Little Stour

Upon leaving Canterbury the river flows on to Fordwich, Britain’s smallest town, where it becomes tidal. It then enters the Lower Stour, a marshland landscape where intensive agriculture contrasts with important wildlife areas. At Stodmarsh National Nature Reserve, superb wetland habitats support internationally important communities of birds, plants and invertebrates. The Lower Stour as a whole is a stronghold for the declining water vole and has seen the return of otters and beavers.

At Pluck’s Gutter, the Great Stour is joined by the Little Stour, and becomes The Stour. From here it flows across a landscape that was once the sea – the Wantsum Channel separated Kent from the Isle of Thanet during the Roman and Early Medieval period. The Richborough and Ebbsfleet area is particularly significant in our history – the traditonal landing place of the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons and St Augustine. Sandwich is a well-preserved medieval town rich in heritage.

Beyond Sandwich, the Stour is near the end of its journey, and what a finale! Here the river and its associated habitats are protected as part of much larger conservation areas. The bird life is second to none and diverse habitats supports a rich variety of plants and insects. At Pegwell Bay, the Stour finally completes its journey to the sea.

For more information on the catchment and all its main rivers, download our leaflet.

Water Framework Directive

The Water Framework Directive (WFD) is a management strategy that takes an integrated approach to looking after our rivers and other bodies of fresh water. It does this by looking at water as a vital part of ecosystems and taking into account the movement of water through the hydrological cycle.

Not only does the WFD require integration of water management but it also requires other environmental priorities, economic considerations and social issues to be considered when setting water management objectives.

Stakeholder engagement and involvement in water management is a key theme of the WFD so consequently ensuring and enabling this participation and influence should be an integral part of the river basin planning process. The WFD provides an overarching framework to protect and improve the aquatic environment through greater integration between water and land management, and to balance this with other environmental, economic and social priorities when setting environmental objectives. This means that close co-operation between public, private and civil society organisations will be necessary.

For more information about the Kentish Stour and its catchment visit the Environment Agency’s Catchment Data Explorer.

Ecological status of the Stour Catchment

Banded demoiselle (photo: Jo Taylor)

When you look at the River Stour and its tributaries they may give the impression of being clean and healthy. But are they? The ‘health’ of a river is determined by its capacity to support a variety of life. This is termed the river’s ‘ecological status’. Under the Water Framework Directive (WFD), rivers are classified by one of five ecological statuses: High, Good, Moderate, Poor and Bad. Good status rivers will support a thriving mix of flora and fauna.

For monitoring and classification purposes the Kentish Stour Catchment is divided into a number of discrete river water bodies: twenty in all. The latest publically available monitoring (2016) indicates that most of these – twelve – are at Moderate status; seven are classified as Poor, and one – the River Dour – is classified as Bad. The KSCP, Environment Agency and other partners are committed to getting as many water bodies as possible to Good status by 2027. This shows we have much work to do to make our rivers healthier for people and wildlife.

So what causes a river to have a poor ecological status? There are a number of factors that impact on a river’s capacity to support life. One of the obvious ones is the chemical make-up of the water. Obviously polluting or contaminating inputs to the river will make it harder for a diverse range of species to survive. Sometimes this is because one species is able to adapt to or tolerate the conditions more than others and will become dominant. This is often the case where watercourses have high nutrient levels. Nutrients can enter the river in a number of ways: from sewage treatment works, from agriculture and industry, and surface water discharges from urban areas.

Phosphate

Phosphate levels are a particular concern in the Stour system. Fortunately when phosphate levels are reduced many species can recover relatively quickly. Over recent years Southern Water Services have invested in phosphate reduction at sewage treatment works across the Stour catchment. We are starting to see the benefits of this investment in lower phosphate levels in our rivers. Farmers are playing their part too: the Catchment Sensitive Farming initiative, overseen by Natural England, has the Stour as a priority, and many farmers are modifying their methods to reduce nutrient inputs to the river. Also, the quality of urban run-off is being improved by using sustainable drainage systems (SuDs). Ashford Borough Council has been at the forefront of developing policy to ensure water is considered at the heart of urban design.

Water use

Another factor that is important is the flow in the river: obviously the more we take out of the river for human, agricultural or industrial consumption, the less there is left in the river to support life. Although most of the water we use in Kent comes out of underground aquifers, these same aquifers feed water into our rivers. That is why it is important for all of us to use water wisely in our homes.

Structures

Another factor that impacts greatly on the Stour catchment is the physical interference of man. Throughout history the river system has been managed by man, whether for drainage, flood risk management, navigation or to power mills. These activities can have a detrimental effect on the river. For example, weir structures often slow the river down to such an extent that silt settles out and smothers the gravel bed. Weirs can also obstruct the migration of fish.

Removal or modification of structures can prove complex due to the complications of ownership as well as the technical difficulties. It can also be expensive. A major obstruction to fish passage was identified at Pledges Mill in the centre of Ashford. In 2013 this structure was modified to allow fish and eel passage as well as improve flow conditions to reduce siltation. This project cost over £200,000 and there are over 30 mills on the Stour system!

Our rivers can also be improved by returning artificial river-banks to a more natural state. Much work has been undertaken throughout Canterbury to achieve this.

Collaboration

We have a target to bring our rivers up to Good status by 2027. Fortunately we are not starting from scratch; much has already been done and much more is planned.

Flooding

Flooding at Hambrook Marshes (photo: Ruth King)

Over the years the floodplains that once protected most settlements from flooding of the River Stour have either been built upon or heavily farmed reducing their ability to cope as effectively with flood waters. However the agricultural areas which remain interspersed amongst the urban centres are still important for flood storage. Where houses have been established on floodplains there is an even greater risk of flooding and adaptions have to be made, for example flood storage reservoirs were completed on the Upper Stour and East Stour in the 1990s, providing better protection for Ashford.

The main flood risk to the River Stour comes from prolonged rainfall whilst high tides can also prevent flood waters draining into the sea. Over the last 60 years the catchment has flooded regularly with nine recorded major flood events, the worst in 2000/01. Due to the five tributaries converging in the town, Ashford has been particularly at risk, but storage reservoirs have helped reduce this . The city of Canterbury has not experienced extensive flooding as most of the river is contained within walls as it flows through the city; however, in 2000 between 50 and 100 properties were flooded in the city centre.

A major change made to the River Stour to prevent flooding at Sandwich was the creation of the Stonar channel. Towards the end of the River Stour’s course the water has to make a winding route to the sea, this long route delays the amount of time the river and any floodwater takes to reach the sea increasing the risk of flooding. In 1776 a flood relief channel called the Stonar Cut was made cutting across the neck of one of the very large hairpin bends towards the end of the river’s course. The gates, now modern flood gates, are opened after prolonged rain meaning that the flow can be diverted down the Stonar Cut direct to the sea. This adaption has meant that around 3,000 acres of land benefit from a reduced risk of flooding.

The Environment Agency is the main organisation responsible for reducing the risk of flooding along the River Stour. The main ways in which they do this are through maintaining existing flood defences and structures, creating new and replacing existing flood defences, forecasting for flooding and sending out warnings when necessary, influencing the planning of new developments near the river, mapping the risk of flooding, providing environmental improvements and strategically planning for long term investment. In order to provide these services the Environment Agency works alongside other organisations such as local councils or governmental advisors such as Natural England.