CHALK STREAMS IN THE STOUR CATCHMENT

THE RARE RIVERS NEAR YOU

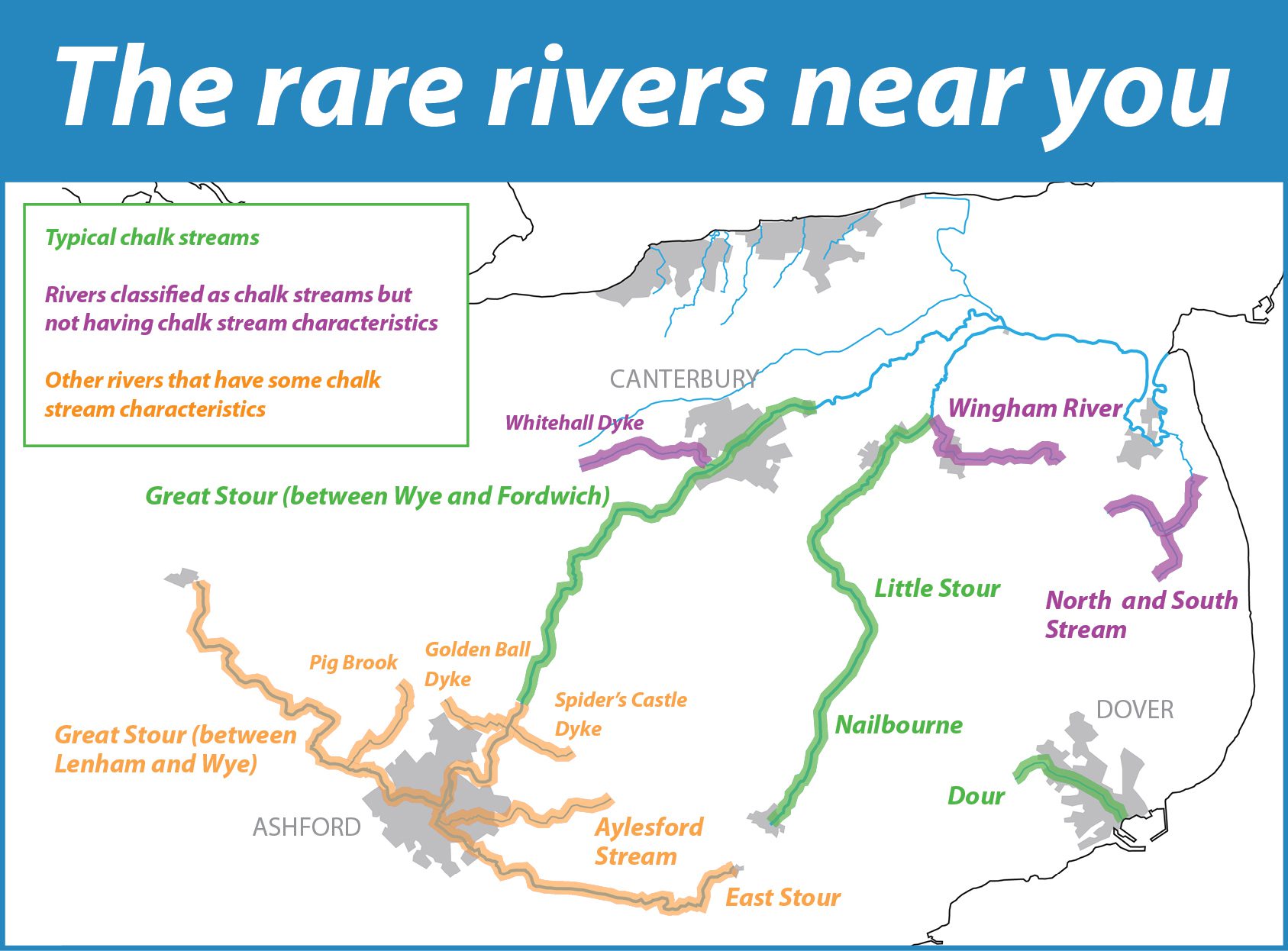

This map shows the chalk streams in the area that the KSCP covers. While some of them are typical chalk streams, others are classified as chalk streams but don’t have chalk stream characteristics. The map also shows rivers that are not classified as chalks streams but have some of their characteristics. Read on to find out more about the individual rivers.

ALL VALUABLE, ALL UNIQUE

Every chalk stream is different. This is because the valleys they flow through are different, and underlying geology varies from place to place. So some rivers have the classic features of a chalk stream – a steady flow of cool, clear, shallow water, and all the characteristic wildlife – while others are less typical. There are four broad types:

Group A – Classic chalk streams

Rivers that are fed by springs rising in chalk rocks, and flow over chalk on the shallow ‘dip’ slope of the Downs, but may later flow over other rock types. An example would be the Nailbourne.

Group B – Mixed geology chalk streams

They are fed by springs that rise in rocks other than chalk, but then flow through the chalk. This is a more unusual type than A, of which the Great Stour is a widely recognised example.

Group C – Scarp slope chalk streams

These rivers rise on the steep ‘scarp’ slope of the Downs and flow for a short distance over chalk, before reaching other rock types. The upper reaches of the Spiders Castle Dyke would be an example.

Group D – Under the ice chalk streams

This group rises on chalk that was directly impacted by glacial action. There are no streams in Kent in this category.

Below are profiles of the chalk streams we have in the Stour Catchment.

GREAT STOUR (BETWEEN ASHFORD AND FORDWICH)

The Great Stour at Godmersham

The Great Stour is not a chalk stream along its whole length. At its source at Lenham, it’s fed by springs rising through clay, not chalk. It then flows across clay and sandstone, but despite this, the Great Stour between Lenham and Ashford has many chalk stream characteristics and is a habitat for typical chalk stream species. In Ashford, it has a major confluence with the East Stour.

A few miles downstream the Great Stour flows into the village of Wye, and it is from this point that it is classed as a chalk stream proper. It flows in a wide valley through the chalk of the Kent Downs, before arriving at the historic city of Canterbury. On the other side of Canterbury, past Fordwich, the river becomes tidal, and the presence of brackish water means it ceases to be a chalk stream.

There are some ways in which the Great Stour is not a typical chalk stream. Water levels are highly variable. The river can rise very quickly, due to the fact that it’s upper reaches are on clay and sandstone, where water levels react strongly to rain. In these ‘spate’ periods, the river receives a lot of silt and doesn’t run clear. Conversely, the river can suffer from periods of low flow, due in part to the heavy demand on the aquifer for drinking water.

Water crowfoot in the Great Stour, Canterbury

Despite this, the Great Stour between Wye and Fordwich is a beautiful chalk stream, with some very aesthetically pleasing stretches, especially when the swathes of snowy white water crowfoot flowers are in bloom. It is home to many of the species in the classic chalk stream fauna, including brown trout, mayflies and kingfishers.

NAILBOURNE

The Nailbourne at Bourne Park (photo: GkgAlf, CC-BY-SA)

The Nailbourne, which flows through the Elham Valley, is a particular type of chalk stream called a winterbourne. Winterbournes are rather mysterious rivers that do not flow all the time.

A winterbourne can be predictable and seasonal (hence the name) or much more intermittent. Flows can also vary from one part of a river to another: water may be running in one stretch, while just a short distance away it’s dry.

The reason for this sporadic character is fluctuation in the water table – where and when it is high enough to meet the stream bed (usually in winter), the river will flow. But variations in local geology and landform lead to inconsistency in where it will flow. Leaky stream beds can also lead to water disappearing back underground.

The Nailbourne has many eccentricities! Its source, at St Eadburgh’s Well in Lyminge, is a constantly flowing, crystal-clear chalk spring. Between Lyminge and Elham the river usually flows throughout the year. Levels are lower in summer and in some years it will dry out completely. Beyond Elham things get much less predictable…

St Eadburgh’s Well, Lyminge (photo: Ian Taylor, CC BY-SA 2.0)

In wetter years, the water table will be high enough for the river to appear between Elham and Bekesbourne, but many winters can pass without any flow at all. If it does flow, it may not flow in all places. In some stretches it will run strongly, in some there will be just shallow standing water, and in others no water at all, with apparently no rhyme or reason to the pattern. This unpredictability of the Nailbourne continues until it meets the Silver Dyke and becomes the Little Stour.

Tradition has it that the intermittent section of the Nailbourne flows once every seven years. Of course it could never have been that predictable, but we can perhaps assume that was a rough average. If there ever was a pattern, climate change is now disrupting it, with successions of dry years with no flow, and unusually wet years causing flooding.

Watch our video about the Nailbourne’s eccentric habits.

LITTLE STOUR

The Little Stour near Littlebourne

The Little Stour is formed by the confluence of the Nailbourne and the Silver Dyke, near Littlebourne. Unlike the Nailbourne, it flows reliably all year round, although summer levels can be low in places.

Local people will know the Little Stour where it flows through Littlebourne and Wickhambreaux and enhances the charm of these pleasant villages. There are lovely, rural riverside walks along the Little Stour, such as that from Seaton towards Preston Marshes. It’s a very attractive river in these stretches – seemingly very natural, with plenty of plant and animal life. But all is not quite as it seems.

Explore Littlebourne and Wickhambreaux and you can’t fail to notice some very prominent buildings – water mills. The mills may be picturesque, but the history of milling has left a legacy of river modification. The natural river channel has been moved, straightened, deepened and generally re-engineered in many places. Manmade structures such as weirs interrupt natural flow and the movement of fish. The Little Stour may look natural but is quite artificial in many ways and is not allowed to behave as a wild river should.

Wickhambreaux water mill (photo: Nick Smith)

Despite this, the Little Stour has retained many features of a chalk stream and is home to many classic chalk stream species. River restoration work has been carried out along two sections near Seaton to try and bring back natural features that were lost in the past.

The other major factor adversely affecting the Little Stour is another river that flows into it – the Wingham River. After this confluence, the character of the Little Stour changes quite drastically. Despite technically being a chalk stream itself, the Wingham introduces poor quality water, and the Little Stour ceases to have any real chalk stream characteristics.

RIVERS CLASSIFIED AS CHALK STREAMS BUT NOT HAVING CHALK STREAM CHARACTERISTICS

Wingham River

The Wingham River is fed by chalk springs and is classified as a chalk stream, but in reality does not have chalk stream characteristics. It is suffering from a number of man-made problems – low flows due to abstraction of drinking water, pollution from sewage works and agriculture, bridges that interfere with its flow. In fact, it may never have had chalk stream character, because it flows over drift deposits thickly overlay the chalk bedrock – it flows over peat soils above Wingham.

North and South Stream

Like the Wingham River, the North and South Stream is a chalk stream in name only. It is classed as a ‘Highly Modified Water Body’ and is quite artificial in many respects, having the character of a marshland drainage channel for the most part. Local coal mining has also impacted it, in the form of saline water getting into the stream, and subsidence that means it needs to be pumped in some areas. However, because there are few man-made structures in the stream, and work has been done to improve water quality, the future is looking better for this watercourse.

Whitehall Dyke

Also known as the Cranburne or Cranbourne, the Whitehall Dyke rises from springs near Denstead Wood in the Blean and flows east towards Harbledown. It then turns south, and downstream of Golden Hill it flows over chalk – this is why it is classified as a chalk stream on some maps. However, it does not have typical chalk stream characteristics, but is well known as a ‘chalybeate’ stream. This means the water contains mineral salts of iron, said to be beneficial to health – chalybeate streams often have reddish, rusty coloured water. These minerals also make the water slightly acidic, so very different to the alkaline waters of a chalk stream.

OTHER RIVERS THAT HAVE SOME CHALK STREAM CHARACTERISTICS

East Stour

Fed by chalk springs emerging near Postling, the East Stour flows across clay and sandstone bedrock for its whole course, so is not a chalk stream. However, it does have some chalk stream character, especially in its upper reaches. In addition, it has been recognised as an ‘active shingle river’. This means its river bed is shaped by natural processes, with gravel and stones being constantly moved by currents. This provides good habitats for fish and other wildlife.

Aylesford Stream

Like the East Stour, the Aylesford Stream is fed by chalk springs and doesn’t flow over chalk. It has some chalk stream characteristics and is good for wildlife in parts. Surprisingly, some of the urban stretches in Ashford are more natural than the rural ones. This is because riverside habitats have often been lost in the countryside because of intensive agriculture, which can also impact water quality.

Pig Brook, Golden Ball Dyke, and Spider’s Castle Dyke (aka Brook Stream)

These three small, colourfully named streams all rise as chalk springs through the chalk, but quickly flow onto sandstone and clay. Some maps show them as chalk streams and others don’t. Not much is known about them, but they are likely to have some chalk stream characteristics, especially in their upper reaches. This is probably true of many other small streams flowing from springs near the foot of the Downs.

The Great Stour between Lenham and Wye also falls into this category, as described above.